From 2016 to 2017, more than 66,000 deaths across the US involved opioid overdoses. In Wisconsin, Kenosha ranked first among the state’s 72 counties for overdose deaths. Community leaders and health experts united rapidly in the fight against the opioid epidemic. Conversations then and now continue to focus on raising the community’s awareness about opioid overdoses.

From 2016 to 2017, more than 66,000 deaths across the US involved opioid overdoses. In Wisconsin, Kenosha ranked first among the state’s 72 counties for overdose deaths. Community leaders and health experts united rapidly in the fight against the opioid epidemic. Conversations then and now continue to focus on raising the community’s awareness about opioid overdoses.

“Opiates” are psychotropic substances derived purely from the opium poppy plant (heroin, morphine) or their synthetic analogues, which are generally referred to as “opioids” (fentanyl, dilaudid, Oxycontin, codeine, Vicodin, Norco). However, “opioids” is now used as the umbrella term for all opiates and opioids.

According to the United State’s Surgeon General’s advisory, two major factors have contributed to the epidemic of overdose deaths: 1) the rapid production of illicitly made fentanyl and other highly potent synthetic opioids; and 2) the increased number of prescribed opioids for long-term pain management.

Fentanyl is a synthetic version of heroin but much stronger and more potent. Fentanyl and other powerful, illicit synthetic opioids are being mixed with heroin; other drugs, such as cocaine; and even pressed into tablets to resemble the appearance of misused prescription pills. This unpredictability in illegal drugs has led to numerous overdose deaths.

In 2012, opioid prescriptions exceeded 250 million in the US alone. The proliferation of prescribed opioids increases both the risk of chemical addiction as well as accidental overdoses amongst individuals, even when taken as prescribed for pain. Anyone taking or using any form of an opioid is at risk of an opioid overdose; however, elevated risk factors for an overdose include: taking larger than usual dosage; using alone; injecting; long-term use; and using after a period of abstinence (recent incarceration or drug rehabilitation program).

Opioids affect various parts of the brain that control functions such as breathing, heartbeat, and emotions. Excessive and prolonged use increases a user’s tolerance. As the tolerance increases, so does the need and the amount of the drug in order to achieve continued effects (“the high”). Because the body is unable to manage this quantity over time, a threshold is breached, and an overdose occurs.

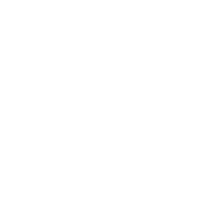

It is important to recognize the signs of an opioid overdose. Kenosha County educates its citizens by the B.L.U.E. acronym:

B: Breathing during an overdose is shallow, gurgling, erratic, or completely absent.

L: Lips and fingertips are blue. This is because of the decrease of oxygen throughout the body.

U: Unresponsive. The victim will not respond to verbal or physical stimulation because the high dose of opioids causes the brain to slow down.

E: Eyes (pupils) are pinpoint. The opioids constrict pupils to an unusually small size.

During an overdose, a pulse may still be present despite an ongoing depletion of oxygen. Therefore, immediate assessment, identification, and action can help save a life. If you encounter someone with a suspected overdose, assess the individual, administer Narcan, dial 9-1-1, and perform rescue breathing if able and needed.

For more information contact:

The Kenosha County Division of Health (262) 605-6741 or,

The AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin (262) 657-6644

A recent survey indicates all of 53% of Americans believe that addiction is a disease. (

A recent survey indicates all of 53% of Americans believe that addiction is a disease. ( There is a lot of confusion in the lay press and among the general public (and even some healthcare professionals) about the various levels of care and treatment options. People mistakenly assume that all individuals with addiction need inpatient detoxification services. The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) has a well validated tool, known as the ASAM Criteria, to determine the appropriate level of care for individuals seeking treatment for addiction.

There is a lot of confusion in the lay press and among the general public (and even some healthcare professionals) about the various levels of care and treatment options. People mistakenly assume that all individuals with addiction need inpatient detoxification services. The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) has a well validated tool, known as the ASAM Criteria, to determine the appropriate level of care for individuals seeking treatment for addiction.

“For patients currently taking high doses of opioids as prescribed for pain, individuals misusing prescription opioids, individuals using illicit opioids such as heroin or fentanyl, health care practitioners, family and friends of people who have an opioid use disorder, and community members who come into contact with people at risk for opioid overdose, knowing how to use naloxone (Narcan) and keeping it within reach can save a life.”

“For patients currently taking high doses of opioids as prescribed for pain, individuals misusing prescription opioids, individuals using illicit opioids such as heroin or fentanyl, health care practitioners, family and friends of people who have an opioid use disorder, and community members who come into contact with people at risk for opioid overdose, knowing how to use naloxone (Narcan) and keeping it within reach can save a life.”  The Kenosha County Substance Abuse Coalition (KCSAC) invites you to start three medication habits:

The Kenosha County Substance Abuse Coalition (KCSAC) invites you to start three medication habits: